The Pros and Cons of Pacing Guides

During the Covid-19 pandemic, pacing guides are becoming a surety of educators’ professional lives. Will the pressure to teach everything before the next test ruin the teaching and learning process?

What are Pacing Guides?

School district leaders develop pacing guides to help educators remain on track and ensure curricular continuity across schools. These guides work similarly to traditional scope-and-sequence documents, which layout expectations of the content to be covered in each subject at each grade level. But today’s pacing guides are distinct because they plan out the subjects and topics that will be on the yearly state test and schedule these topics before the spring testing dates. Many pacing guides are tied to benchmark assessments that take place quarterly or more often, further delineating what educators must teach and when they must teach it. Many pacing guides specify the number of days, class periods, or even minutes that educators should devote to each topic.

Whether the amount of content to cover is decided by a textbook, scope, sequence, or pacing guide, educators today face heightened pressure to cover all the topics likely to be on the annual state test before the spring testing date.

The Pressure of Staying on Track

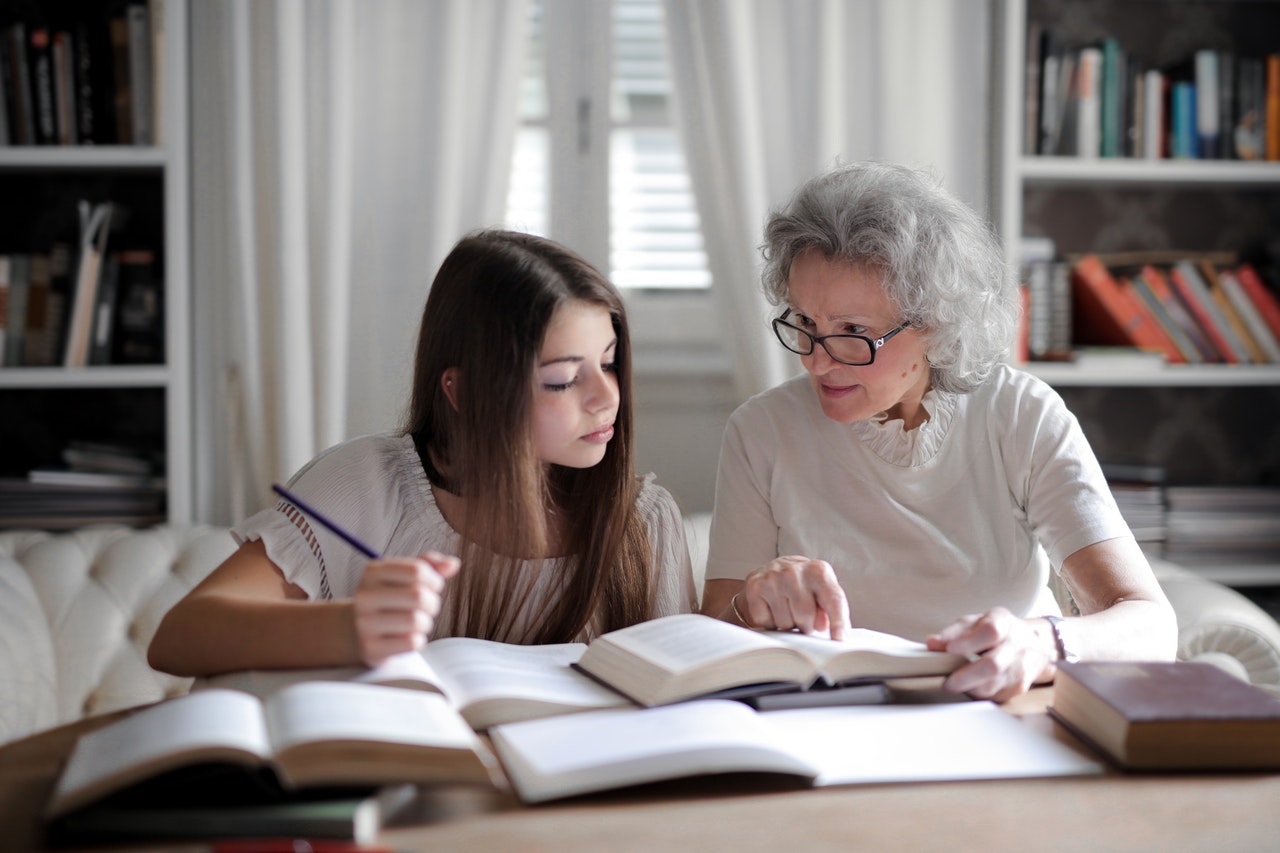

Teachers do not want to handicap their learners—or their school’s ranking—by skipping topics. For new educators, pacing guides are often the primary source of information on what their school expects them to teach. Yet, most educators confront the inescapable reality that they simply don’t have enough time to adequately cover all the content, particularly if they need remediation. Educators are caught in a precarious position: Slow down and risk lack of coverage, or speed up and sacrifice depth of learning.

Research suggests that pacing guides pressure educators to cover all the content specified and that educators attempt to meet this demand in many ways. One is to pay more attention to tested subjects, giving less attention to science, music, art, and social studies.

A common response is to rely on educator-centered lessons that seem more efficient and predictable than learner-centered lessons. Engaging learners in more time-consuming, cognitively demanding activities that nurture deep understanding tends to fall by the wayside. Long-term projects, like reading and analyzing entire books, are bypassed.

Although all educators are pressed for time, educators with predominantly low-performing and minority learners are far more likely to drop cognitively demanding activities than are other educators. The former feel more stress and are likely to focus on traditional forms of educator-centered instruction. Some districts utilize pacing guides as a tool to monitor educators’ adherence to a prescribed, centralized curriculum. This monitoring tends to lead to narrow content and teaching strategies.

The quality of pacing guides and how educators respond to them vary greatly, however. Research on new educators, for example, points to their need for curricular guidance. One study finds that new educators can benefit from resources such as pacing guides designed to help them figure out what to teach and how to teach it.

Concluding thoughts

Pacing guides are not a bad idea. Their effects o on then contingent on their design and how district and school leaders utilize them. The most effective pacing guides emphasize curriculum guidance instead of prescriptive pacing; these guides focus on central ideas and provide links to exemplary curriculum contents, lessons, and teaching strategies.

Guides like these embody what many experienced educators do when they plan their curriculum for the year: They chunk it, put topics in a sensible order, decide what resources to draw on, and develop a good idea of how long distinct elements will take. They also let for some unpredictability depending on their particular mix of learners.

Constructive pacing guides assume differences in educators, learners, and school contexts. They adjust expectations through continuous revisions based on input from educators. Most essential, they encourage instruction that challenges learners beyond the content of the test.