When Trump proposed a wall and California tore one down

Prop 58 bilingual, dual-language programs improve education prospects for all kids. Next stop: finding teachers

Kindergarten classes at Ernest R. Geddes Elementary School in Baldwin Park, Calif., are taught primarily in Spanish as part of the school’s bilingual program. Photo: Sarah Garland)

As the election results were rolling in across the country signaling that Donald Trump would become the 45th president of the United States, nearly three-quarters of Californians had voted to restore bilingual education in California.

The Trump campaign had been overtly anti-immigrant, while the restoration of bilingual education was an affirmation of the valuing of the children of immigrants. How could California and the nation be at such great odds?

In 1976, California was one of the first states in the nation to pass legislation making it a requirement for schools to provide bilingual education to its English learners (ELs). The rationale for these programs was that such instruction would combat discrimination against immigrant children and support development of a stronger self- concept, in addition to providing instruction in a language the children could understand, thereby avoiding school failure.

Related: California voters overturn English-only instruction law

While there wasn’t a large body of research on any of this, it made intuitive as well as logical sense. This remained the policy in California until the passage of a voter initiative in 1998 entitled Proposition 227, or “English for the Children,” effectively prohibited bilingual instruction in most cases.

The seemingly slow acquisition of English and the low achievement of EL kids were blamed on bilingual education, even though no more than 30 percent of ELs were ever provided bilingual instruction, mostly because of a lack of credentialed bilingual teachers.

The solution was to immerse the students in a cold bath of English, eschewing instruction in a language they could actually understand.

The snake-oil salesman who convinced the voters in 1998 that with English-only instruction ELs would become proficient in English in one year and raise their academic performance at the same time was not unlike Donald Trump. Even at the time, there was sufficient research to suggest that the first of these promises was unlikely, and the second simply impossible.

Related: How can being bilingual be an asset for white students and a deficit for immigrants?

Ron Unz manufactured statistics that could never be verified: “The majority of English learners are in bilingual programs,” “hundreds of thousands of these students languish in classes where only Spanish is taught, not English.”

These remarks aren’t dissimilar to the claims of Donald Trump that Mexican immigrants are “rapists and criminals,” that he will build a wall to shut out our neighbors to the south, or that he will rescind the program that allows young “Dreamers” (young people brought to the U.S. as children) to go to college or work without fear of deportation — no verifiable facts, no specificity about how the proposals would actually work.

The ban on bilingual instruction passed with more than 60 percent of the vote – mostly by voters who had never seen a bilingual program (as was the case with Unz) or even understood how they worked. After five years, the state’s commissioned evaluation of the impact of Proposition 227 found no significant difference in outcomes for English learners as a result of the new law, but it did “conclude that Proposition 227 focused on the wrong issue.”

Bilingual education was not the problem. Nonetheless, California, home of more children of immigrants than any other state, continued to live with the virtual ban on bilingual instruction until this year.

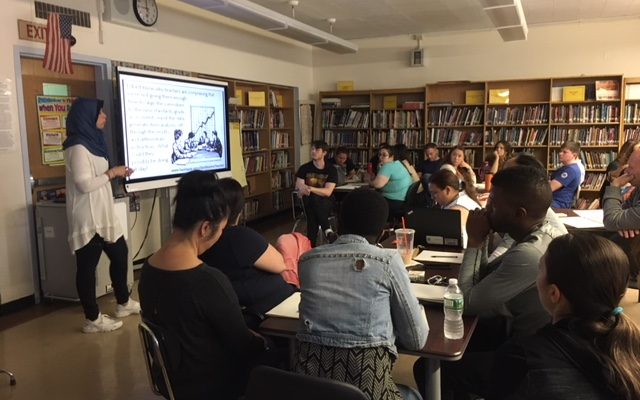

Proposition 58, “The Multilingual Education Initiative,” lifted the ban and expands access to bilingual (usually targeted to English learners) and dual-language programs (that incorporate both English learners and English speakers wanting to learn a second language).

During the last 18 years, research has been conducted that shows significant benefits to multilingual instruction. Canadians have long been researching the cognitive benefits and concluding that learning in more than one language effectively made students “smarter” – they demonstrated a greater capacity for focused attention and avoidance of distractions. However, this research never had a major impact on policy in the U.S., perhaps because we have always considered our situation to be very different from Canada’s.

In recent years, longitudinal research – following the same children over their entire school career, from kindergarten to high school — comparing those in bilingual and dual-language programs to those in English-only classrooms, has concluded that while the bilinguals start slower, they end with superior outcomes in English, and Latino students perform better in both English and math when enrolled in bilingual programs.

Other research has shown that the children of immigrants who attain literacy in their home language actually earn more once in the workforce, and, again, in the case of Latinos go on to four-year universities at higher rates than those who lose that language ability.

Over the last two decades, too many children have been denied an education that could have conferred real benefits, and too many have been left behind. But perhaps equally important, California’s classrooms have been emptied of bilingual teachers. Although the demand for these programs continues to grow, less than one-third as many young people prepare to become bilingual teachers today as did in 1998. Why prepare for a job that doesn’t exist?

The dearth of prepared teachers will be a significant impediment to mounting these highly desired programs even as they have become once again legal.

Meantime, we have to hope that false promises and unverifiable claims made by presidential candidates do not tear at the fabric of this nation, a nation of immigrants.

Patricia Gándara is Research Professor and Co-Director of the Civil Rights Project at UCLA. She is also Chair of the Working Group on Education for the University of California-Mexico Initiative.