What Teachers Need to Know About Student Privacy

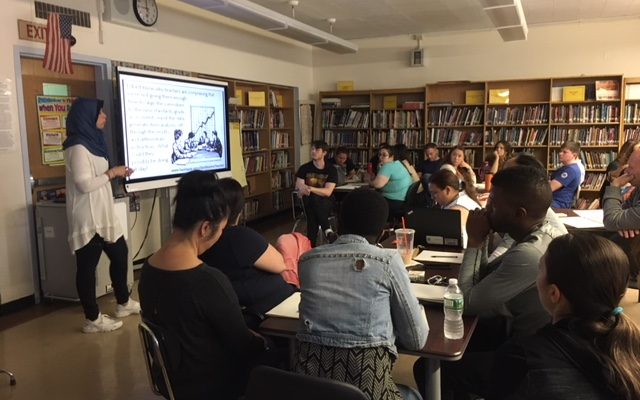

There is often conflict between students’ right to privacy and a school districts’ responsibility to keep their students safe. However, most districts now have a set of rules from local, state, and national authorities governing the resolution of that tension.

Personal histories and records exist for every student and teacher at a school. This history, in the form of school records, test scores, and the opinions of teachers and mentors, can have a huge impact on students’ futures. On the basis of these assessments about students’ potential and overall disposition, life-changing decisions are made. Students’ history could determine what colleges they are admitted to, the privileges that they are allowed, or even the jobs they may eventually be able to attain.

Consequently, the proper exchange of this information is very important; the information must be exchanged through transparent and impartial means. This is even more relevant considering the fact that the kind of information that exists in school records may not be completely true and bears the risk of being misinterpreted if it falls into the wrong hands. This was realized in the 1970s, when instances of parents and students being denied access to their school records became public.

The immediate response to this problem was the passing of the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA, or the Buckley Amendment, as it is popularly known) by the U.S. Congress in 1974. The act makes clear who may have access to a student’s records and who may not. The move was largely beneficial for parents who were previously denied access to records that were very likely to affect their children’s lives. The act made it mandatory for schools to share all information about students with their parents, when requested. It also required schools to explain or interpret the recorded observations to parents, with the failure to do so resulting in federal funds being denied to the school. At the same time, the act serves in the best interests of teachers. It clearly denies parents the right to inspect a teacher’s or an administrator’s unofficial records.

The Buckley amendment applies to all schools that receive federal money. The act has been a promising step in ensuring transparency in dealing with and handling student’s records. Aspects of the act, such as the confidentiality granted to both parties, make it stand out as a reformative measure in ensuring the right to privacy for individuals wanting to be educated.

Here is how FERPA empowers parents and guardians and puts them in a better position than they were previously:

- Parents and guardians can inspect their child’s school records.

- The act ensures that information about students under 18 years of age can’t be passed on without parental consent.

- Parents have the right to challenge the accuracy of information at any point in time and to request a hearing to contest such information.

- A legal route to correct children’s school records and to place a statement of disagreement in student records is now open to parents.

- Parents can singlehandedly decide who can access the information about their child.

- In cases where parents find any discrepancies, they can always file a complaint with the U.S. Department of Education to seek relief in the civil courts.

Student Privacy and Drug Testing

In 2002, the U.S. Supreme Court, in the case of the Board of Education of Independent School District No. 92 of Pottawatomie County et al. v. Earls et al., examined the validity of the 1998 Student Activities Drug Testing Policy of the Tecumseh, Oklahoma, school district. This policy asked students to undergo mandatory urine analysis for illegal drugs like cocaine, marijuana, and opiates before participating in competitive activities in school such as choir, athletics, cheerleading, and other extracurricular activities. Offended by this policy, and considering it to be a violation of their privacy, two students named Lindsay Earls and Daniel James of Tecumseh High School took the school authorities to court. Their point was that, in view of the students’ Fourth Amendment rights to protection from “unreasonable searches” and the requirement of “probable cause,” their being subjected to such examinations was a violation of their lawful rights. The premise put forth was that there existed no “probable cause” of drug usage by students participating in extracurricular activities, and consequently the urine analysis that was being imposed on them was an “unreasonable search.”

With respect to “unreasonable search,” the right to privacy of the individual concerned is of key concern for the courts. The court ruled that because students in public schools are in “temporary custody of the state,” their right to privacy is limited in this case. The court also ruled that, in this case, urine analysis is acceptable because the manner in which the school district collected the urine sample was not an invasion of privacy. As for the issue of drug testing and the presence of a “probable cause,” the court’s stance is clear. Several court cases have ruled that a warrant and the presence of a “probable cause” is not required for students in public schools, because that requirement would complicate the matter and interfere with disciplinary procedures. This means that school authorities can search any student who participates in extracurricular activities, without need for a concrete “probable cause.” The only requirement is that the search be carried out in a reasonable manner.

In Board of Education of Independent School District No. 92 of Pottawatomie County et al. v. Earls et al., the court ruled that any public school district can formulate a student drug-testing policy for itself, and that this would not in any way interfere with the Fourth Amendment rights of students. The Office of National Drug Control Policy even went so far as to issue a booklet to local school districts propagating drug testing for students. This has proven to be a great drug-taking deterrent for students in schools. Still, many groups, such as the National Education Association and the American Academy of Pediatrics, were not satisfied with the court’s verdict, as they were concerned about privacy issues and that students could find such testing invasive. Despite this, most school districts have adopted the Tecumseh School District’s stated policies in an effort to stay out of legal troubles.

While students may feel that their school or teacher is just trying to impose rules for no reason, educators know that their boundaries are set for the students’ benefit. As an educator, you must make sure you understand your school’s policies surrounding student privacy and know how to implement those policies in the kindest, most professional way possible.