Pass or Fail: Early Intervention and School Partnerships

In this multi-part series, I provide a dissection of the phenomenon of retention and social promotion. Also, I describe the many different methods that would improve student instruction in classrooms and eliminate the need for retention and social promotion if combined effectively.

While reading this series, periodically ask yourself this question: Why are educators, parents and the American public complicit in a practice that does demonstrable harm to children and the competitive future of the country?

“Teamwork makes the dream work.” A catchy saying that holds a lot of validity when talking about early intervention programs and school-based services.

In order for early intervention to serve students better, an appropriate relationship between early intervention organizations and schools is absolutely necessary. The transition procedure from early intervention to school should be streamlined. There is also a need for far greater consistency between early-intervention programs and school-age programs, as well as between programs in different regions, including across school districts and states.

A Working Partnership

Early intervention and school-based service providers must work together to support children because of the unavoidable, but often unaddressed, reality that children do not arrive at school with empty minds. The educator’s task is not to fill the mind (it is already full), but to enlarge its capacity – the capacity for knowledge and critical thinking, for analysis, and for understanding. For this to be achieved, though, and for children to truly be the subject of their educational journey, a working partnership must be developed. Early-intervention service providers and programs that take on the challenge of supporting children beyond the early developmental phases, will need to foster a collaborative spirit.

Well-Defined Standards

However, a partnership between early intervention and schools cannot occur without an appropriate knowledge foundation. It is crucial that educators at all levels understand how early experiences and early-childhood development are essential to later learning. The broader point is that there needs to be a relationship between the curriculum and the realities that children construct for themselves. This depends on clear collaboration between school and early intervention, beginning with the establishment and maintenance of clear standards for supports.

While early intervention programs and school-based programs must continue to address students as individuals, the specific needs of each child should also be addressed. Standards may dictate the type of supports to be used, and what kind of services are to be offered. They may also, for the sake of managing resources, dictate what levels of supports are to be offered to students based on need assessments. The types and levels of support may be customized within parameters defined at a higher administrative level.

Intervention Protocols

Ideally, there should be protocols for requesting that certain procedures be overlooked on a case-by-case basis, so that individual students receive supports tailored to their needs. A child might, for instance, receive more behavioral supports in school or their early childhood environment than would be warranted based on assessment results and diagnostic findings. The reason for this could be that the child was demonstrating a behavior of particular concern and that needed additional support.

Additional Considerations

Although it is hardly possible to do away with budgetary considerations in the planning of early intervention and school-based supports, the general rule should be established that early intervention services and supports in early school years are likely to produce a much higher return on investment than those applied later in a child’s school career. All educators, but especially special education teachers, must respect the long-term consequences of withholding services and supports that they require to succeed in school, as well as curtail disruptive or self-destructive behavior.

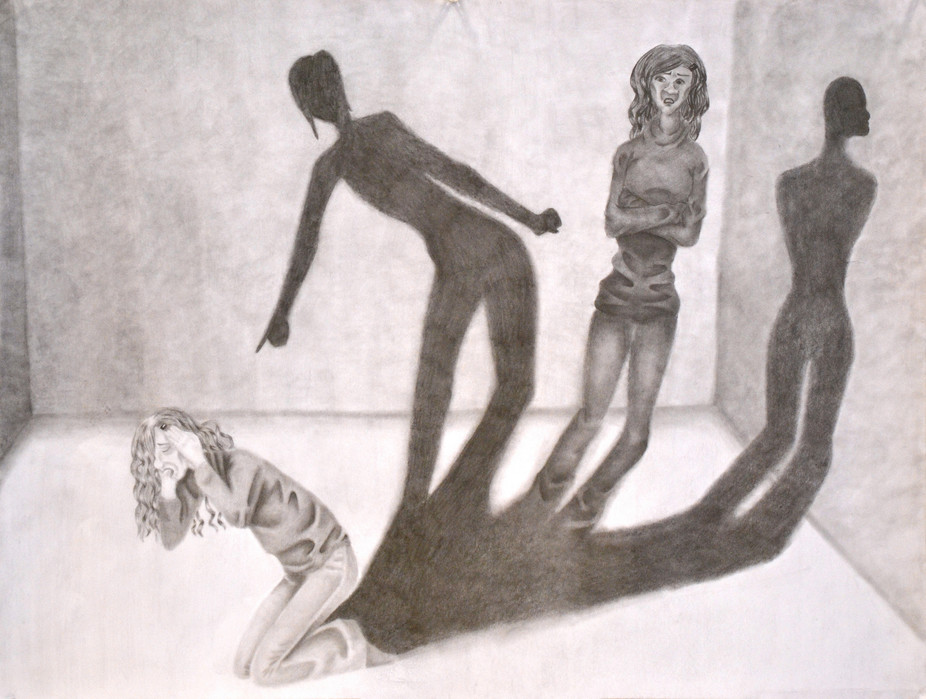

Even with the removal of graded systems and an end to the problems of retention and social promotion, school failure will persist because of counterproductive pressures and inadequate support. Children do not arrive with empty heads; they have expectations, standards of thinking, and processes of learning that, if ignored in the school setting, will cause academic failure and, perhaps, the decision to drop out of school. Students who cannot find the intersection between the curriculum and the structures in their heads – and this includes students with special needs – are likely to become part of that estimated 10 percent of the school population that either drops out of school altogether, or fails to graduate from high school.

Do the costs of early intervention programs outweigh the costs to parents, teachers, society and the student themselves, if they are not adequately prepared academically?