Explainer: what is all the fuss about the Common Core?

Ken Libby, University of Colorado

When it comes to US public education, few topics engender such heated debate as a new set of maths and English standards for school children known as the Common Core.

Since the final standards were released in 2010, they have been adopted by 44 states and the District of Columbia. This marks a departure from the long history in the US of leaving most educational standards up to the whims of states and local school districts, resulting in different standards in every state for kindergarten to grade 12.

The Common Core counts supporters and critics in both of the two major US political parties. This makes the conversation about the standards quite messy and interesting – especially given the upcoming congressional elections in November.

Fighting ‘ObamaCore’

Although moderate conservatives generally favour the Common Core, those further to the right, like the Tea Party, portray the new standards as inappropriate meddling by the federal government. Some engage in wild conspiracy theories, and attack the standards as part of a broader anti-public school agenda.

The fight over the US’s recent changes to healthcare policy, Affordable Care Act (sometimes referred to as “ObamaCare”), provides a way for some conservative activists to jump into the Common Core fray by claiming the new standards are the educational equivalent (“ObamaCore”). It’s a poor comparison, but permits easy entry into the debate for those with little substantive knowledge.

Left-leaning critics cite concerns about the potential for private companies (such as publishing group Pearson) to profit from the Common Core as a reason for rejecting the new standards.

Criticism of the standards is coming in all shapes and sizes.

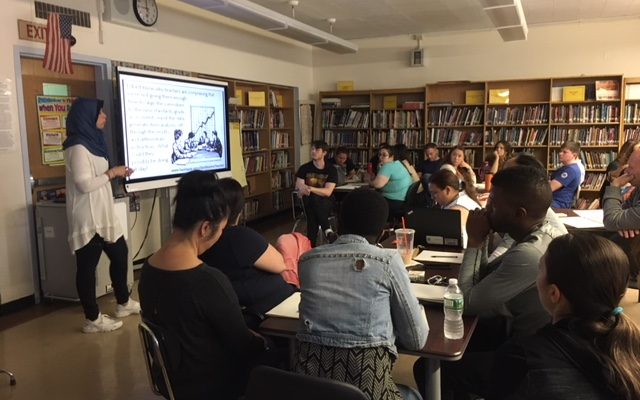

amerigus/WWYD , CC BY

There are also concerns as to whether the standards for early elementary students are developmentally inappropriate. Others dismiss the new standards as a solution to a problem that does not exist, or a band-aid for much bigger problems, like the high child poverty rate in the US.

Some critics of the Common Core view it as further cementing the use (and misuse) of standardised testing in American schools.

State-driven testing

In addition to the new standards, two consortia of states – Smarter Balanced and the Partnership for Assessment and Readiness for College and Careers – have been working to develop tests tied to the standards. However, some states, such as Kansas, have opted to develop their own assessments.

These new and ostensibly better assessments created by the two consortia may provide some real advantages compared to previous tests. However, early trials of assessments tied to the Common Core indicate up to 70% of students in New York may not receive a passing mark given the more challenging nature of the standards. While that may well paint a reasonably accurate picture of how many students can truly meet the new standards, it is a politically tenuous position to maintain.

Supporters, on the other hand, claim the standards are more challenging than previous state standards (and they are, at least for most states). They also say that the standards will better prepare students for college-level work, and create a more level playing field for children across the country.

The shift to the Common Core comes as states pursue several other policy changes, including teacher evaluations based in part on student progress on standardised tests. These new evaluations attempt to use statistical models to calculate a measure of teacher quality based on how much a teacher’s students improve their performance on standardised tests, usually controlling for a host of other variables.

What teachers think

Pursuing both the new Common Core standards and teacher evaluations at the same time is worrying, especially if teachers and schools are not adequately prepared to help students reach the goals of the new standards.

While teachers generally support the common core, they also express reservations about implementation. A poll conducted in July 2013 by the largest teachers union, the National Education Association (NEA), indicated that teachers wanted more time to collaborate with colleagues about the new standards, updated resources, and enhanced technology for the classroom.

With each state and school district responsible for implementation, the degree to which teachers feel supported (or not) varies greatly. Heads of both the NEA and the second largest teachers union, the American Federation of Teachers, have expressed concerns about Common Core implementation in recent months.

Personally, I do not consider myself a strong supporter of the common core. Nor am I an opponent. Although some critics make wild charges and engage in conspiracy theories, there are certainly legitimate concerns about the changes.

Implementation seems rushed in far too many places, leaving teachers and students inadequately prepared for the shift. If equity across the country were truly a concern, we would talk about how states do an exceedingly poor job of financing schools equitably, giving fewer resources to districts populated with low-income students and racial minorities. We would also tackle the inequitable distribution of teachers and various out-of-school factors – poverty, residential segregation, inequality and racism.

With more states shifting to the new standards and assessments in the coming year, the Common Core will likely remain an important issue in US public education and political debate. The standards themselves are rarely discussed – in large part because the biggest concerns are about related (and perhaps intertwined) issues like testing, teacher evaluations, and implementation.

![]()

Ken Libby, PhD student studying educational foundations, policy and practice, University of Colorado

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.