How Did We Get Here? Part VI: Unified, Then Divided, Public Schools

This is one of a multi-part series on the progression of education policies in the U.S. from its founding. Click here to see a list of all the posts in this series.

By Matthew Lynch

Public education in the U.S. remained primarily unchanged throughout the first and second World Wars. Improvements in communication, particularly through radio transmissions, brought schools into the worldwide on goings of the battles. Though not part of any textbooks or measured testing, wartime knowledge became something of value in public schools and patriotism grew in its role as a virtue. Unlike the Civil War, which divided the nation, the World Wars in the first half of the 20th century knit the union more tightly together. As millions of men fought outside U.S. soil, women filled in job roles and kids continued to attend school. Going to school and learning was in its own way a sign of solidarity.

The united feel of public education was all but destroyed in the 1950s and 1960s as issues of desegregation plagued the nation. Many Americans cheered the changes, of course, but there were enough opposing desegregation to make it a bleak time in U.S. public school history. If public education was, after all, meant to provide common knowledge, and life skills, in equal ways to all children in America then the theory of “separate but equal” certainly needed to be disposed. Change is difficult though, even in one of the most progressive nations in the world. The World War I and II-era solidarity in public school classrooms faded, replaced for arguably the first time in U.S. history with controversy within the schools. As the adults of the nation debated what should be allowed in schools and what was best for students, the children lived it out.

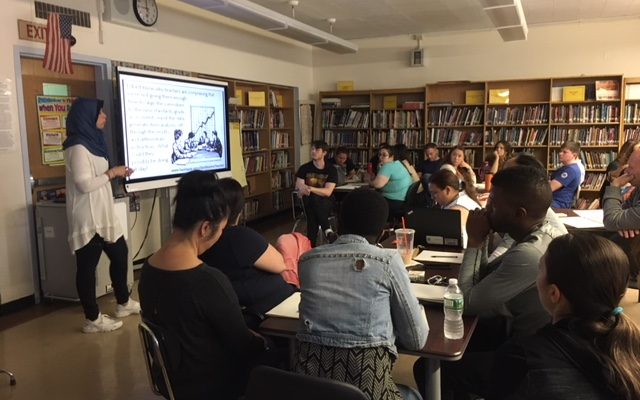

These two decades mark an important change in the role and perception of public schools in America. Before schools started taking on bigger issues like desegregation, and abuse, and childhood hunger, they were places that served the needs of the nation. That tide turned in the mid-1900s as public schools began to lead instead of just follow. Public schools stopped adhering to what was dictated for its next generation in terms of learning and citizenship and began to blaze a trail for the rest of society where collective belief systems were concerned. It may have been too late to change the minds of disenfranchised adults who had grown up accepting their worlds in a particular way, but it was still early for students. Needed change was not going to happen overnight but it was needed just the same.

Schools became the vehicles for future change, starting with the youth of the nation. The focus was no longer just on economics, or raising ideal citizens; core ideologies were being shaped in public school classrooms across the nation.

This characteristic of public schools is still evident today. Take anti-bullying campaigns, for example, particularly as they relate to lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender students. While many parents (and even some school boards) are fighting against anti-bullying policies that are designed to protect LGBT students, schools across the country are adopting them at a rapid pace anyway. The same is true of healthy eating programs and the push to get kids away from television and computers and involved in active pursuits instead. Schools cannot change what is being taught at home, or even what students themselves believe. Yet by leading change through example and actual policy, the thought is that future generations will have a different approach to important issues than their parents did. Like the socially conscious efforts of Dewey, public schools establish principles that then govern a particular group of K-12 students as adults.

The 1970s brought even more equality in public schools with the passage of the Education for All Handicapped Children Act. This was the first federal regulation that mandated that public schools accepting federal funding also provide a free education, and meals, to children with mental or physical disabilities. It was not enough to simply accept the students; schools had to create a teaching plan that would give these students as close to a typical education as their non-handicapped peers. Though separate classrooms were inherent to the plan, schools were instructed to keep special education students as near to their peers as possible. By this token, public schools became even stronger when it came to truly opening their doors for all students, and being a right of American life. Follow my series on the progress of the U.S. educational system to learn more about where we’ve been, and where we need to go, as collective educators.