Intelligence in America: Time to Test Something New

Measuring the progress of any endeavor requires a definition of success.

Education, by its very nature, is difficult to ascribe a single definition of success; “making people smarter” is far too broad and subjective, while “increasing the IQs of students” is perhaps too esoteric and subject to debate over the role of genetics and other uncontrollable factors.

Measuring progress is similarly fraught in the academic sector. Grades have been a target of considerable suspicion for some time now, and rightly so: everything from grade inflation to instructor subjectivity makes grades an altogether blunt and misleading metric. There again, what do we suppose grades to be a reflection of? Intelligence? Learning? Student performance? Knowledge retention? The creation of new cognitive pathways and connections between existing knowledge and new subjects?

Testing for Cognition First

The foibles of old fashioned metrics for academic performance, combined with the new potential opened up by both modern pedagogy and technology, have combined to deliver a novel answer to the question of how to measure success in education. Suppose we were to quantify and then measure cognition, the functions of the brain and evidence of thought itself, as expressed by students?

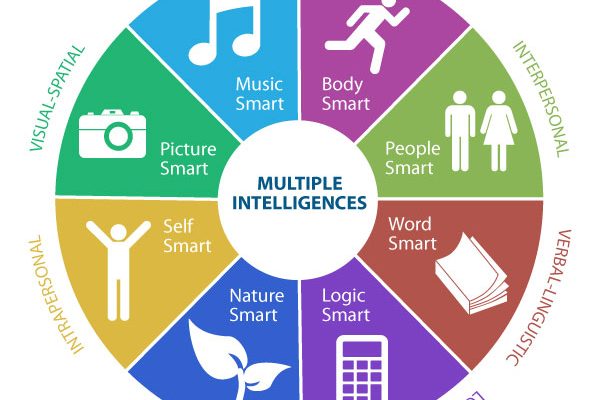

Cognitive testing in the classroom doesn’t necessitate the acquisition of CAT scans or neural mapping technology. Rather, it begins with acknowledging that “intelligence” takes many forms, and that learning, by extension, will likely look and feel distinct based on the individual intelligence (or intelligences) of a given student. The purpose of cognitive testing, in a sense, is to begin measuring education by beginning with the “How” of learning, and then moving on to quantify “How Much” of that type, or those types, of learning are taking place.

When teachers, curricula, and schools place more emphasis on the discovery of student learning habits, they may be better positioned to monitor learning according to the skills, needs, and limitations of each individual student. This doesn’t mean abandoning standards wholesale; rather, it recognizes that standards, particularly standardized tests, need to reflect at least some of the variability that can’t simply be taught out of students. A narrow view of intelligence yields a narrow appreciation for different skills, perspectives, and contributions.

In politics, education is broadly acknowledged as critical, irreplaceable, and central to the American dream. It is one of the few subjects on which partisan interests align, at least in theory: education is a good thing, and civil society, as well as the economy, needs more and better education. If education strives to impart knowledge and skills, it ought to do so according to how students will be the most receptive to such instruction. That means tracking cognition first, and defining intelligence from that starting point. Problem-solving starts with thinking about a problem, then applying skills and knowledge to overcome it. Education, similarly, might start with thinking before jumping to assessment.

Controlling for Usefulness in Teaching Skills

Skill loss can be a sign of cognitive decline. Consider how Alzheimer’s patients lose track of their memories, and over time, their ability to safely and independently function. Or, how stroke victims must sometimes relearn basic skills, like speaking, reading, or writing. There is certainly a physical dimension to cognitive performance, and instances of skill loss make it painfully apparent.

However, skill loss can also be anthropological. As technology evolves, the value of human skill changes in response — or, put differently, “we shape our tools; thereafter, our tools shape us.”

What counts as basic intelligence, as measured by skills and performance potential, is highly dependent on context. A century and a half ago, the ability to drive a car bordered on irrelevant for the masses, as cars were a rare and expensive novelty. By the middle of the 20th century, learning to drive was a rite of passage as well as a necessity; to drive was to attain freedom and independence, to be a true American. Cars were a subject of great importance, and knowledge of their operation and construction a point of pride and social belonging.

By the beginning of the 21st century, any understanding of how a manual transmission works is well on its way to extinction, as automatic transmission has largely displaced the technology. In fact, automation threatens driving as an altogether superfluous skill, along with all the training, socialization, and individual status it used to impart.

All this to say that when we seek to measure intelligence, at least in the classroom, we ought to have some notion of usefulness. In an age of nearly universal internet access, is memorization a good proxy for intelligence, or is it just another skill in decline thanks to technology? American schools are historically deficient in teaching living essentials, yet simultaneously preoccupied with indoctrinating skills and trivia of questionable value.

Intelligence and Knowing How to Survive

Politicians and social critics like to point out that America is increasingly lagging behind other nations in areas like science, math, and technical education. But we need not look outside our borders to see significant gaps in our educational system.

Financial literacy among Americans is staggeringly low: some two-thirds of the population can’t demonstrate a basic understanding of financial topics. Small wonder, then, that so many families and individuals are taking on too many loans, over-leveraging credit, and generally living beyond their means. The American dream may put great stock in education, but in practice it is built on borrowing and juggling debt.

First things first: if we want American students to be competitive around the world, they need to know how to survive in modern America. It is fine to suggest we need more STEM graduates coming out of our universities, but we might also want to reconsider whether the student loan system is preying on the financial illiteracy of these very same students. What competitive advantage do we gain from all the STEM graduates in the country being underwater with student loans?

Tests in schools — most especially standardized tests seeking to measure some nebulous metric as “intelligence” — often bear little resemblance to any real-world scenario. Tests are just tests, despite the stakes they often carry; practical applications may take an entirely different set of skills and knowledge that schools don’t always adequately prepare students to demonstrate. Not only do we use the wrong system to benchmark education, we have the wrong benchmarks in place compared to what students will actually need when they go from the classroom to the workplace, the bank, or even to university.

Intelligence has individual elements, as well as social elements, that both need better representation in our schools. We need to be more realistic, and more receptive, to analyzing how students think, so we can better help them learn. In doing so, we can gain better insight into how much progress they make and better equip them with the skills and knowledge they lack, but require to succeed.