Do school vouchers improve results? It depends on what we ask

Joshua Cowen, Michigan State University

A set of reports on Louisiana’s statewide school voucher program recently revealed a number of important features of that program’s operation and overall performance.

The most startling of these reports indicated that students who used school vouchers performed much worse on standardized tests than those who remained in traditional public schools.

This result echoes evidence presented last month from a separate team of scholars, who found negative impacts after one year of voucher use in Louisiana. The latest study not only confirmed that finding, but showed the pattern persisting – albeit less severely – after two years of voucher use as well.

School vouchers provide publicly funded tuition – typically for low-income families – to attend private schools. And these reports provide the first evidence that participating in such a system may harm kids’ academic achievement, at least in math.

As a researcher who studies both vouchers and other forms of school choice such as charter schools (independently operated public schools) I believe the new Louisiana studies are important to longstanding debates over the extent to which such choice enhances academic outcomes.

It may be tempting to use this news as an argument against vouchers, especially because the evidence is drawn from the most sophisticated research tools available to scholars who study these programs. However, it should be stressed that test scores provide only one indicator of program success or failure.

Impact of vouchers

The motivation for school voucher programs dates back to the 1950s, when the economist Milton Friedman began to argue that parents should have opportunities to choose between different providers of education for their children.

School vouchers provide publicly funded tuition – typically for low-income families – to attend private schools.

401(K) 2012, CC BY-SA

The first school voucher program began in 1990 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Over the years since, especially in the last decade, voucher or voucher-like systems have spread to 24 states, all of which differ individually on some key details such as the number of children who will be eligible for participation and the maximum amount of tuition available to these students.

In Louisiana, policymakers introduced vouchers in 2008 in New Orleans as part of a series of reforms following Hurricane Katrina’s devastation of the city and the city’s school system. In 2012, vouchers became available statewide.

As with many public programs, policymakers turn to researchers to help determine how well school vouchers work. This is true not only in Louisiana, but elsewhere as well.

And part of what makes the Louisiana results so newsworthy – but also why voucher critics should pause before leaning too heavily on the latest reports – is that many of these studies conducted in other locations, such as Charlotte, Milwaukee, Washington, D.C. and New York City, for example, found the opposite pattern. In these studies, students who used vouchers to attend private school tended to have higher test scores as a result.

The answers are not that simple

The question is whether test scores are the only way to judge schools and school performance.

It is true that public schools have to test their students, so using a similar metric is a reasonable, relative comparison between public and private schools. But test scores, while important, do not necessarily provide an absolute appraisal of the strengths and weaknesses of voucher programs in a large education system.

What is the best way to judge schools’ performance?

woodleywonderworks, CC BY

First, we know from earlier studies that student attainment levels – high school graduation or enrollment in post-secondary education – may be higher among voucher users even when test score differences between them and their public school counterparts are nonexistent.

Whether this means that private schools are especially good at preparing kids to graduate and attend college or that they simply prioritize such success more than other outcomes is still unclear. But we see similar patterns in charter schools too: a number of studies have shown that charter school students have a higher chance of high school graduation or college enrollment even when their test scores do not differ on average from their traditional public school counterparts.

In the Louisiana context, the researchers also found more nuanced results when they posed a number of other questions.

When researchers examined, for example, whether competition from private schools pressed nearby public schools to improve performance, they found that the test scores of students in these competing schools did indeed increase, albeit modestly.

When they asked whether the declines in voucher users’ tests scores were present in noncognitive student outcomes (such as grit, self-esteem, and political tolerance), they found both public and private school students had similar levels on those indicators.

Each of these questions provides a different way of assessing the overall impact of the voucher program both on students who use them and on students in the surrounding communities as well.

Weighing other factors

More generally, it’s important to remember that voucher programs operate differently in different places.

In Louisiana, for example, one prominent explanation for the negative test scores is that heavy regulation of private providers keeps the best schools in that sector away from offering seats to voucher users. But in Wisconsin, we know that some regulations, such as requiring private schools to publicly report the academic performance of their voucher users, actually increased test scores.

Other state laws determine who’s eligible to use a voucher in the first place. In some states, vouchers exist expressly for kids with special academic needs; in others, low-income families are eligible as well.

Again, this implies that we have to be very careful. It is not as simple as taking evidence from one state and expecting the same results, good or bad, in another.

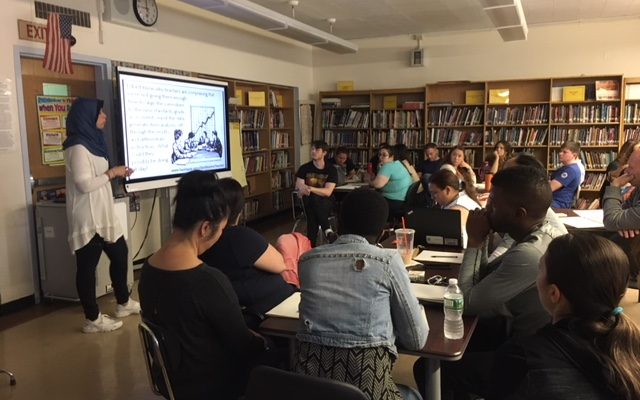

Little is known about teachers in schools that accept vouchers.

EarthFix, CC BY-NC

Apart from differences between states, there are other things to consider about the way voucher programs operate.

We know surprisingly little about teachers in schools that accept vouchers. State oversight of private school teachers is far less – in some places practically nonexistent – than for public school teachers.

Researchers are beginning, for example, to devote considerable effort to understanding who teaches in public charter schools. Answering that question in different voucher programs will help explain differences in students’ outcomes between private and public schools, both within and between different states.

Finally, we need to consider not only which students accept and benefit from a voucher, but also the extent to those who do attend private school – or any nontraditional alternative – are actually able to do so over the long term.

The evidence we have from places like Milwaukee and Washington, D.C. suggests substantial turnover in voucher programs, with minority students and students with the lowest test scores leaving private schools.

All of this is to say that when it comes to educating kids, what we know about school vouchers depends on what we ask. And what we ask should be informed not only by traditional academic outcomes, such as test scores, but also by a new understanding of the many different ways that schools can contribute to student success.

![]()

Joshua Cowen, Associate Professor of Educational Policy, Michigan State University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.