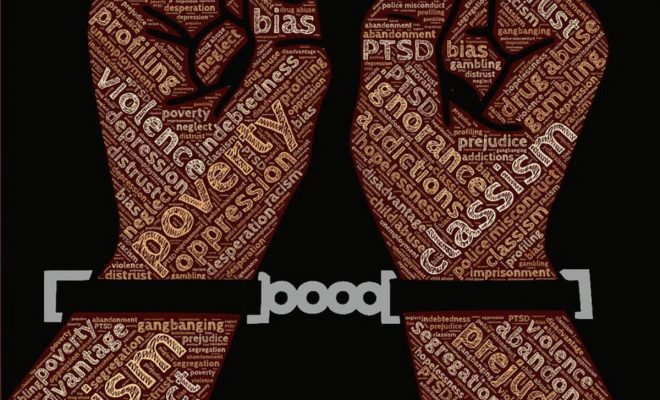

Black Boys in Crisis: How to Solve the Black Boy-Special Education Problem

In this series, appropriately titled “Black Boys in Crisis,” I highlight the problems facing black boys in education today, as well as provide clear steps that will lead us out of the crisis.

The statistics on high numbers of black and Latino boys in special education programs is more than an interesting tidbit – it’s a call to action. What can we do to identify true learning delays and isolated behavior problems and disseminate them from disabilities?

Early intervention.

Here we are again, using the word intervention to identify an actionable step to improve academic success for black boys. There’s a reason intervention is more than just a buzz word; catching developmental delays early on shows the greatest promise for improvement. This starts before Kindergarten in the Head Start programs across the country and state-run intervention initiatives, like Florida’s Early Step program. Investments in early education have shown to return as much as $17.07 to society on every dollar spent.

Doctors are at the frontlines of the early intervention referral program and know what warning signs to heed, even when parents may not. The time between a doctor’s referral and the start of services can take several months, depending on the state and resources available, and that is precious time in the development of the child. For early intervention to have its biggest impact, the time between suspicion of delays and start of services must be accelerated. Children who are diagnosed with developmental delays by the age of 3 have the best shot at catching up to their peers by the time they reach Kindergarten. After that age cutoff, the likelihood of children keeping with their classmates fades.

When black boys with obvious developmental delays do wind up in Kindergarten classes, however, it’s vital that teachers spot it. This takes specialized training that is updated and repeated throughout a teacher’s career to address the ever shifting issues facing our youngest students. Change also calls on teachers to look beyond their preconceived notions of learning disabilities to determine which students may have a shot at overcoming the hurdles and avoiding the special education label. Rather than grouping students for life, we need to start looking at some academic and behavioral issues as temporary and applying the resources we can to guide students over the hurdles.

Mainstreaming

The idea that special education students should be removed in order to learn best is actually being flipped on its head due to recent research. A study done at The Ohio State University found that special-needs preschoolers who spent at least some time in classrooms with typical students had language scores 40 percent higher than peers who remained in special-needs only settings. The improvements extended beyond the special-needs kids, as well. The highly-skilled peers also improved their reading skills over rates from when no special-needs students were in the classroom. In short, the “weakest link” mentality did not apply.

It’s true that true special needs students need a different educational plan than their mainstream peers and that ultimately means some time outside the typical classroom. Special needs students should never be completely isolated from their peers though, and in cases where the classification is not accurate, that will become apparent as children overcome the developmental hurdles they face.

Cultural awareness

It’s extremely vital that teachers have a knowledge set of students outside of their own life experiences and an understanding of how the way those children behave is impacted by it. Students without the benefit of preschool or parents who had the time and availability to teach them literacy basics will not perform as well when they arrive in classrooms. Next to their peers who have had such advantages, they may even seem delayed. It’s important to note, however, that the first required schooling for American children is Kindergarten. There is a push for a lot more learning a lot earlier, but from a purely legal standpoint, kids are not required to show up to learn until they are Kindergarten age (which is defined as late as 7 years old in some states). The cultural expectation is that these children should already know a lot when they arrive, both academically and socially, but for children from families who waited for that Kindergarten age, it truly is the first time they’ve seen a classroom.

Universal preschool in states like Florida, Illinois and Oklahoma can help bridge that learning and socialization gap for low-income families but once again, these programs are voluntary. It’s not fair or accurate for educators to assume that even in states when preschool education is affordable or free, parents are taking advantage of it. There are many factors that go into the level of education families pursue for their children before the school years officially start. Compared to peers, this puts children with no prior classroom experience at a disadvantage. But compared to what is actually required of the students when they show up on that first day of Kindergarten, these blank slate students are exactly where they need to be from a learning perspective.

With that in mind, early grade educators must know the difference between true special education warning signals and a kid who just needs to catch up. There are evaluation processes in place beyond the teacher but it starts in a classroom. This isn’t to say that teachers should try to champion behavior or learning issues they cannot change but merely for them to be aware that not all children have the advantages of an early learning foundation. That doesn’t mean necessarily that all of those children have special education needs.

What do you think? How should schools address this issue?